Managing Your Workplace Retirement Plan – Part II

Americans have a potential retirement crisis on their hands. As we discussed in Part I of this article, the move from company-sponsored pension plans to employee contribution plans (e.g. 401(k) and 403(b) plans) transferred the responsibility to save for retirement from the employer to employees. What is beginning to become evident is that individuals aren’t all that good at saving for their own retirement. A quick look at statistical data reveals just how big this looming retirement problem is for the majority of Americans. According to this CNBC article, almost 50% of households have no retirement savings at all. Even if we exclude everyone that doesn’t have anything saved for retirement, the median retirement savings of the households with retirement plans is still only about $60,000. That’s not going to last very long once people stop earning an income and start using that money to pay the bills.

As a reminder, the world’s view of retirement is not the same as the biblical model. The world seeks to accumulate savings in order to avoid work in the later years and use that time to eat, drink and be merry, much like the rich fool in Luke 12. The Bible, on the other hand, describes work as a gift from God and a way for us to serve as long as we are able. Retirement savings are accumulated for the purpose of providing for our families once we are no longer able to work. The difficult question for all of us is how much will we need.

How Much Do We Need?

Most articles take the approach that we’ll need to replace a percentage of our income at retirement (I often see 70-75% of income as the replacement goal). I prefer to base retirement need on actual spending rather than income because our spending should be independent of how much we make. It’s not uncommon to have two families with the same amount of income only to find that one is spending twice as much as the other. So, I would recommend you estimate the amount of income you will need to sustain your current lifestyle at retirement. This projection will require you to anticipate any debts that will be paid off and new expenses that will come up during retirement. If you’re more than a few years from retirement, you can take your current spending amount and inflate (for now you could use 2% or 3% inflation) that over the number of years to retirement to get to an anticipated spending budget for the year you retire.

Once you have the income you need to replace, you can then deduct off any other sources of retirement income, such as a company pension or social security income. However, I find that most people under 50 years old don’t put a lot of faith in social security income and generally set their savings goal without considering any future benefits from it.

The income number you come up with will allow you to calculate a rough estimate of the savings it would take to generate that amount of income. There are many ways to do this calculation and each has its own set of assumptions. To keep it easy for this discussion, we’ll simply use a consistent withdrawal percentage that will allow principal to not be touched and even grow a little each year to offset inflation costs. After all, retirement can be a long period of time and once you start spending down your savings, the fear of outliving your savings becomes very real. It is one of the most common fears given by retirees.

You may have heard of the 4% withdrawal rule, which seems to be popular in financial articles. The 4% rule says we can safely take 4% from our retirement accounts each year and still leave the principal intact. I find a 4% withdrawal rate a bit aggressive in light of today’s low interest rates and wouldn’t be comfortable with anything over 3.5%. I’m actually going to use a 3.33% withdrawal rate because it makes the math easier. With a 3.33% withdrawal rate, we can take the income we need to replace and multiply it by 30 to come up with the savings requirement. For example, if we need to replace income of $50,000 per year, it will take roughly $1,500,000 ($50,000 x 30) to produce that amount of income indefinitely.

A smaller amount might be able to get us through our retirement years, but once we start dipping into the principal, the savings start to dwindle faster every year. I would rather aim for a higher amount and then give it away if I don’t need it for retirement. Unfortunately, based on the previous savings statistics, most Americans aren’t even remotely close to what they need to provide for their families in retirement.

The Value of Time

Individuals tend to underestimate the importance of contributing to a 401(k) or other workplace retirement plan in their early working years. Sometimes the media doesn’t help matters. I’ve actually read columns advising young people to spend everything they earn to have fun in their 20s and worry about saving later in life. This kind of advice can have big consequences down the road.

As we’ve seen already, the amount we need to save for retirement is a big number. In order to get to that amount, most of us will need the help of time and compound interest. This is why it’s so important to start saving as soon as we get our first job. For most people entering the workforce, it wouldn’t be that difficult to shave off a few dollars from each paycheck. It’s the whole out-of-sight, out-of-mind concept. Unfortunately, most young people don’t do that and they soon develop a taste for the lifestyle the full check can provide. That makes it harder to save for retirement in the future. My advice for young people entering the workforce is to live below your means for the first couple of years and use any excess income to build a solid financial foundation (pay off debt, build an emergency fund and start funding your retirement).

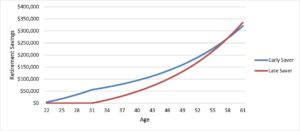

The following chart illustrates the drastic effect compound interest can have on a retirement plan. It shows how a little saved early in your working years can accumulate to the same amount as a much larger amount saved over the later years of your career. The specific assumptions are listed below the chart.

Early Saver

- Saves $4,000/year from age 22 to 31 (10 Years)

- Total Contributions = $40,000

- Investment Return = 6%

- Balance at age 61 = $320,984

Late Saver

- Saves $4,000/year from age 32 to 61 (30 years)

- Total Contributions = $120,000

- Investment Return = 6%

- Balance at age 61 = $335,207

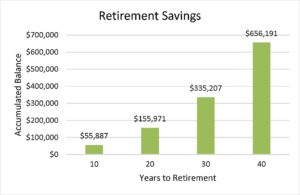

Let’s look at the effects of time on retirement savings in a different way. The following chart illustrates the amount a person will accumulate at retirement if they save $4,000 each year and earn a 6% return over various lengths of time ranging from 10 to 40 years. The difference in the ending balances is quite substantial and it all boils down to how early a person started saving. The obvious conclusion is that we should start saving as much as we can and do it as soon as we can.

Use Realistic Return Assumptions

Sadly, many individuals believe they’re saving enough for retirement because they listen to the talking heads for investment advice and then run retirement calculations based on bad assumptions. The false hope provided by unrealistically high investment returns is a serious problem. Take a second and think of the rate of return assumption you would use today if you were running a retirement plan calculation. Was the return that came to mind 10% or greater? If so, you’re not alone, but you are among those that have been misled to believe those returns are realistic.

In reality, future return projections for money invested in the S&P 500 today are somewhere between 6% and 7%, depending on who you listen to. The analysts I trust are predicting closer to 6%, while a quick internet search will lead you to people that are predicting a rate closer to 7%. These are predictions for the average return a person can expect over the next 20 to 30 years if they invest all their money in the S&P 500, which is representative of large US company stocks. This future expected return is not all that different from what we have experienced in the recent past. Over the last 15 years, the S&P 500 has only averaged 6.69%. Another thing to remember is that this is the expected return for people fully invested in the stock market. Most people are taking less risk than that and as a result can expect even lower returns since risk and return go hand in hand.

If you’ve been expecting your account to grow at 10-12% per year from now until retirement based on what you hear on the radio, you will likely end up with less than you have planned because those returns simply aren’t realistic in today’s investment world. Investment return projections need to take into account things like inflation rates and current market valuations. With inflation and interest rates being next to nothing today and the stock market being near all-time highs, it’s not realistic to assume you’re going to average more than 10% on your investments unless something drastically changes.

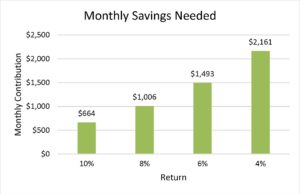

To further show the importance of realistic assumptions, consider the following example. This chart illustrates the monthly contribution a person with 30 years until retirement would need to make in order to accumulate $1,500,000 for retirement under various return assumptions.

This example shows us the importance of return expectations. The difference in required monthly contributions for a person earning 6% instead of 10% is over $800 per month. Investment returns will have a profound impact on your retirement, so make sure you’re being realistic.

Conclusion

Hopefully, this article will raise a few new issues for you to consider. Whether you’re the person not saving for retirement or you’re the one comforted by unrealistic return assumptions, it’s never too late to change your course. With employer pension plans becoming rare and the uncertainty of the future of social security, we can’t rely on anyone else to plan for our retirement. If we fail to take responsibility, we are going to find ourselves at retirement age without enough resources to provide for our families. Planning for retirement isn’t about getting rich and it’s not a contradiction to our faith. We can honor God in the way we spend our money, the way we give our money and also in the way we save our money. We just need to make sure we’re driven by pure motives while always acknowledging that He is the owner of it all.

Brad Graber, CFP® has been working with clients on personal financial planning and investment issues since 1996. He invests his time mentoring and educating individuals on ways to be better stewards of the resources God has entrusted to them.

***Disclaimers: The information contained in this article is general in nature and is provided for informational purposes only. I cannot guarantee that all information is accurate, complete, or timely. Any performance related material is for information purposes only. Past performance is no indication of future results and should not be used for making investment decisions. Performance data was provided by Morningstar. The information in this article should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular investment. Please seek out professional investment advice before investing.

Hello,

I am planning to retire this summer and wondered if you have advice on leaving the 401k with the company or rolling it into an IRA. Also should I take my retirement as a fixed monthly amount or roll that into an IRA.

Thanks, Bill

Your last few sentences were my favorite: Planning for retirement isn’t about getting rich and it’s not a contradiction to our faith. We can honor God in the way we spend our money, the way we give our money and also in the way we save our money. We just need to make sure we’re driven by pure motives while always acknowledging that He is the owner of it all.

During the 1990’s, I dutifully contributed 7% to the company’s 401K. There were limited options, and after a decade, I realized that, due to changes of carriers every year or so, the fees charged against my retirement account actully even cut into my contributions, so that I would have been money ahead to put my money in the bank after tax. Sorry to say, this has colored my opinion of the whole forced 401K thing. After that time, on occasion, I contributed the minimim allowed by my employers. After a layoff, the next full-time permanent job I took, I contributed 10-20% until that layoff. If nothing else, it bolstered the account when I rolled it out into IRA. I found that I did not have time to manage the portfolio and still put in the 48-60 hour work weeks demanded to hold down a job. So I have had real ups and downs in the portion of my portfolio tied to stocks. One section I left alone on a 2020-dated retirement fund. It has performed kind of so-so. Reading about the various “bail-in” situations in Europe and S. America, I have not been keen to put money in 401K this time around. Of course, with time basically running out, there is little difference on the return no matter where I put it. So we are paying tax and saving in a bank account/CD. Realizing that even this (due to to our currency values) is uncertain, we live as frugally as possible while still contributing to the needs of the saints. It is true that one is a fool to trust in his money.